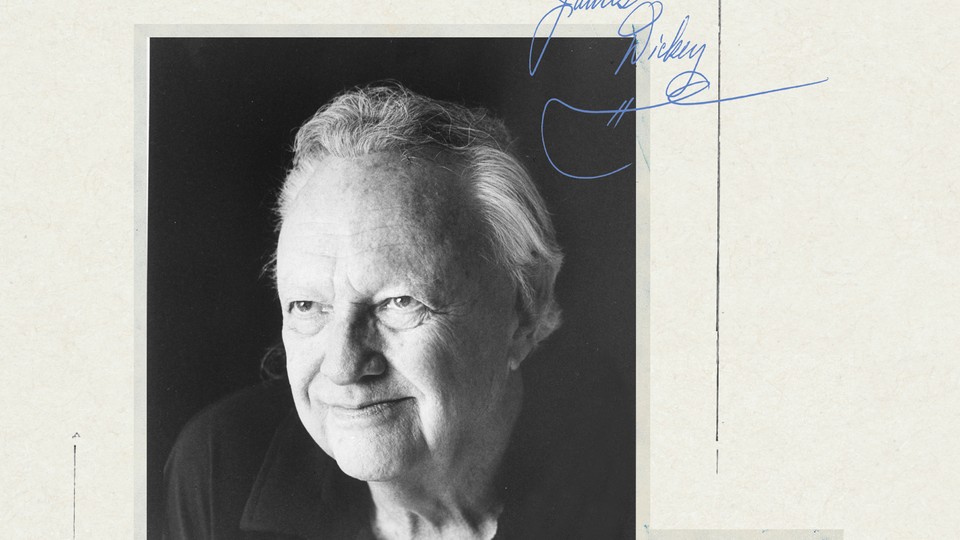

If you asked 10 Americans, “Who was James Dickey?,” my guess is that half would shrug, four would identify him as the author of the novel and movie Deliverance, and the tenth might venture, “Didn’t he read a poem at Jimmy Carter’s inauguration?” or “Wasn’t he our poet laureate back in the 1960s?”

My theoretical estimate would, I think, depress James Dickey, born 100 years ago this February 2, for he wanted above all else to be remembered as a poet. He was the victim of his own success (and excess), having pulled off the neat trick of eclipsing his fame as arguably America’s greatest living poet with a novel about four buddies on a canoe trip that turns very, very weird. (“Squeal like a pig!”)

In honor of his centennial, I laid flowers on his grave in the serene, bird-loud cemetery three miles from where I live in coastal South Carolina. The gravestone is terse: Poet, Father of Bronwen, Kevin and Christopher, and is inscribed,

I move at the heart of the world

Standing there and recalling the time I first met him made me think of a couplet in Thomas Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard”:

Perhaps in this neglected spot is laid

Some heart once pregnant with celestial fire

The occasion of that meeting was the launch of Apollo 7 in 1968 at Cape Kennedy, in Florida. Life magazine had commissioned the poetry consultant to the Library of Congress—America’s de facto poet laureate before we officially had one—to commemorate the occasion with a poem.

I was 16. My father had brought me along. It was an earth-shaking event. Literally. As the ground shook beneath our feet, I watched as an armadillo, a creature that has been around for about 35 million years and was no doubt thinking, Again?, grumpily waddled out of the marsh in search of less apocalyptic quarters.

Recognizing my father among the VIPs, Dickey approached, hand outstretched, grinning. Pup whispered to me, “James Dickey. Very-big-deal poet.”

I’d never met a poet before, much less a very-big-deal one. He was a physical big deal, too: 6 foot 3, with the frame of a former athlete. Sensing my nervousness, Mr. Dickey bent to shake my hand, his grin now a headlight beam, and said in an exuberant Georgia drawl suffused with bourbon—it was 9 a.m.; I was impressed—“Ah have a Christopher, too.”

He had me at hello. I wanted to know everything about James Dickey.

[Read: To a beginning poet, aged sixty]

In time, I learned that he’d been a college track star; a decorated combat aviator in World War II and Korea; a serious bowhunter and guitar player; and a Homeric drinker and lover. He ticked all the boxes. The vibe was unmistakable: Here was America’s Byron.

His Apollo 7 poem was a curtain-raiser for what lay ahead for me:

They plunge with all of us—up from the

flame-trench, up from the Launch Umbilical Tower,

up from the elk and the butterfly, up from

the meadows and rivers and mountains and the beds

of wives into the universal cavern, into the

mathematical abyss, to find us—and return,

to tell us what we will be.

As any southerner might say, “If that ain’t poetry, you can kiss my ass.”

Jim Dickey was a capital-b Bard, not one to stop by woods on a snowy evening, wander lonely as a cloud, or compare thee to a summer’s day.

“The Shark’s Parlor” opens with two buddies baiting a drop-forged hook with a run-over collie pup and tossing it off the porch of an aunt’s beachfront house. The poem concludes with the hammerhead shark they catch, turning Auntie’s parlor into an abattoir, smashing it to smithereens and spewing gore over family keepsakes and gewgaws.

His odd head full of crashed jelly-glass splinters and radio tubes thrashing

Among the pages of fan magazines all the movie stars drenched in sea-blood

“Falling” is based on a news story about a flight attendant who got sucked out the door of an airliner at 1,500 feet, stripped of her clothes and stockings as she plunged to her death. “The Firebombing” is about dropping napalm on civilians, not exactly a poetical comfort zone in the 1960s; the incineration described in the poem takes place two decades earlier, during World War II, as 1,000-pound bombs are released from Dickey’s P-61 Night Fighter.

Gun down

The engines, the eight blades sighing

For the moment when the roofs will connect

Their flames, and make a town burning with all

American fire

“The Eye-Beaters,” acknowledged as one of his finest poems, was inspired by a visit to a home for blind children. Some of them would punch their eyeballs to produce sensations of color.

I wrote my senior paper on Dickey. In an importunity that makes me wince even now, a half century later, I sent him a list of interview questions. He had more pressing things to attend to, like, say, going over the galleys of his forthcoming novel, Deliverance, than a tedious request from a high-school senior with a literary man-crush. (One last question, Mr. Dickey: Have you ever taken hallucinogens?) But 10 days later, there in my mailbox was a thick envelope from Columbia, South Carolina, with three single-spaced typed pages. (As to my question: Yes, once. Peyote.)

His kindness to his students at the University of South Carolina was legendary. James Dickey had more protégés than the Pied Piper. Among them was the novelist Pat Conroy. I blush an even deeper shade of crimson to reveal that, a decade after my questionnaire, my talent for importunity unabated, I sent Dickey a galley of my first book, asking if he might, um, contribute a blurb.

He was now James Dickey, author of the novel Deliverance, serialized in The Atlantic, which also published many of his poems; screenwriter of the movie based on the novel; and the actor who briefly but indelibly played the part of the sheriff who suspects that these suburbanite canoeists aren’t leveling with him about what happened on the river. As my father would put it, James Dickey was now a very, very big deal. But his talent for generosity had not diminished, and in due course 150 words of praise arrived that I can but won’t recite from memory. What a generous soul he was!

His son Christopher, now alas deceased, wrote a fine but often painful-to-read memoir about the downside of his father’s great success with Deliverance. In an oral history about the filming of the movie, Christopher recalled: “With fame came a particular kind of indulgence. People want poets to be bigger than life, to be outrageous, memorable, excessive. They will give them more than enough to drink. They will sleep with them. They will tell stories about them. And all that is seductive for both the poet and his audience. What Deliverance did was take that to a whole new level that was destructive for my father.”

Outrageous, memorable, and excessive he was. And everyone who knew James Dickey had a “James Dickey story” to tell. George Garrett, the novelist (Death of the Fox) and Dickey’s colleague on the USC English faculty, had many in his repertoire. Most could not be called flattering, and do not need retelling on Mr. Dickey’s centennial. But this one I cherish:

Garrett and Dickey were on an elevator. A student standing behind them nudged his companion and whispered audibly, “Know who that is?” Dickey looked at Garrett and winked. “That’s the guy who played the sheriff in Deliverance,” the student said. “The elevator stopped,” Garrett went on, “and we were pushed out by the tide of students. ‘Wait a minute! Wait just a big minute,’ Jim was calling to everybody, nobody in particular. ‘There’s a whole lot more to me than just that.’”

There sure was. I’ll close with my own favorite James Dickey story, which I heard from the lips of Dan Rowan of Laugh-In fame, a lovely soul.

Dickey was guest of honor at Rowan’s summer camp in the California redwoods.

“I woke up early, about six,” Rowan said. “I was getting the fire going for breakfast. Suddenly I became aware of this presence behind me.

“I turned. And there’s James Dickey. He was a great big man. He had on this ratty old terry-cloth bathrobe that didn’t even come down to his knees. It was kind of a sight.

“I said to him, ‘Good morning, Jim!’ He let out this sound, almost like a bear growl. He was looking a bit ragged from the night before.

“Our routine in camp is to serve Ramos Gin Fizzes at breakfast. So I said to him, ‘Jim, may I make you a fizz?’”

“Well,” Rowan said, “this look of … I’d almost call it contempt came over him. He stared at me. ‘A fee-yuz?’ he said. So he goes behind the bar, the whole time maintaining eye contact with me. Pulls down a highball glass and a half-gallon bottle of Wild Turkey. Fills the glass—to the brim—and drinks it all down in one go. Slams the empty glass on the counter and says, ‘Now I will have a fee-yuz.’”

At the grave, I left the flowers, congratulated Mr. Dickey on his centennial, and thanked him for his many kindnesses to me. At home, I looked up the line quoted on his gravestone. It’s from the last stanza of “In the Tree House at Night.”

My green, graceful bones fill the air

With sleeping birds. Alone, alone

And with them I move gently.

I move at the heart of the world.

Strange, to be remembered for “Squeal like a pig” rather than for this. Stranger still: The oink line wasn’t in his script. It was improvised on the spot. No one present, even the director, was ever able to remember who came up with it. It was just to give “Mountain Man” a line of dialogue as he set about making James Dickey immortal.